Just as drawing can help someone truly see an object, transcribing a handwritten document into typed text can help a person truly read it. That is why I encourage clients to take the time to key in the text of handwritten genealogical records they gather in their research. Whether it’s a census record, passenger list, or deed, transcribing documents into word processing software or a spreadsheet not only puts research on solid footing, it just might also provide leads for further exploration.

Don’t let the task intimidate you! Handwriting from centuries ago can be very difficult to read, with letter shapes, punctuation, and turns of phrase that may be unfamiliar. Messy handwriting and poor image quality often make the work that much harder. But with a little bit of study and the mastery of certain tricks (such as finding the same or similar letters in other parts of the document, looking up guessed-at words and names online, and recognizing templated text), you can soon decipher more than you thought you could.

I have extensive experience with transcribing genealogical records and other historical documents. This work includes a three-year batch of letters from a Civil War soldier, and a series of courtship letters from a 19th-century widower to his future second wife. If you feel daunted by tackling transcription on your own, consider getting started by engaging Modern Memoirs’ transcription services. We can help you advance your research by bringing important details into focus, which may uncover something entirely new.

Transcribing documents is valuable because it (literally) spells out the key information needed to study the events of an ancestor’s life: their name in all its variations; age; birthplace; occupation; and nuclear family members. Transcription highlights the consistencies between documents that confirm that the same (correct) individual or family group is studied over time, while also revealing any inconsistencies that need to be investigated and explained. Additionally, transcription prompts the organization of findings to formulate a timeline of an ancestor’s life while putting research findings into a format that can be searched by you and shared with others. But what’s more, transcribing documents may end up illuminating additional, helpful pieces of information held in the original documents.

For example, a census listing might reveal the name of a boarder who turns out to be one of your ancestor’s previously “lost” nephews. Or perhaps a marriage record will reveal a witness who turns up as the caretaker of the couple’s orphaned children later in life. Or maybe a deed names an abutting neighbor who migrated with your ancestor from one section of the country to another.

In other words, transcription may assist you with direct ancestry research while also providing information about extended family, friends, and associates that can indirectly take research to a whole new level. I am eager to help Modern Memoirs clients with this rewarding work, whether or not it leads to a larger book-publishing project.

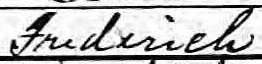

1900 U.S. census for Lamotte, Jackson County, Iowa. This section shows Henry, Mary, Emma, and Frederich Ahlers. Henry and Mary are two of my maternal great-great grandparents and Frederich was their son (my great-grandfather). I transcribed Frederich’s name with an “h” at the end, even though Ancestry.com indexed it with a “k.” That’s because, elsewhere on the page, I noticed that the census taker wrote the letter “k” very distinctly in the word “clerk” and it doesn’t look like the ending of “Frederich.” See below.