Carell Laurent published her book entitled “Pignics” and What Holds Us Together with Modern Memoirs in 2023. This cookbook took nine months from the day she first contacted us to the day books arrived on her doorstep. We asked Laurent to reflect on what the publication process was like for her, and what it has meant to share her book with others.

1. Your cookbook is organized into collections of recipes from the many places you lived with your family as your father’s work with the United Nations from 1960 to 1986 took you to Ghana, Madagascar, New York, Sri Lanka, and Haiti. Each section is introduced with stories and memories from those places. How did you come to choose this format—part memoir, part how-to—for your book?

Carell Laurent: Entertaining was an important part of my family’s time overseas. My parents were naturally very hospitable, and they both enjoyed opening our home(s) to friends and neighbors, believing this to be a positive way to share one’s culture with others.

Over the years, my brothers and I often shared stories of our lives overseas, and although most of our children had the pleasure of knowing their grandparents, I wanted to document some of those stories so that they will be preserved in the future. I recognized that often the stories we would tell about a place included food and get-togethers. The book’s sections on cocktails, dinners, teas, etc., just seemed to make sense in my mind as I recalled the foods we enjoyed in the different places we lived. We certainly had cocktail parties in Tananarive, Madagascar, but what I remember joyously from those days are the “musical soiree” dinners. What I remember from Accra, Ghana is running around with my brothers between the kitchen and the garden, tasting from the cocktail trays. So, it made sense in my mind to divide chapters accordingly.

2. Explain the title of your book. In your life, how does food connect you, not only with your family, but with people of other cultures?

No matter where we would end up as adults, we were bound together by those memories from Madagascar or Ghana.

Carell Laurent: Regarding the first word of the title, my children and my brothers’ children started calling the barbecues at my parents’ farm “pignics” instead of “picnics” because often pork was grilled or barbecued or roasted at these events, and we would eat outdoors picnic style.

As I mentioned above, I come from a home that really valued and appreciated different cultures. There were aspects of growing up in different countries that may have appeared to be difficult to some, but although we may have missed out on some things, we were very close as a family, and that closeness sustained us. My brothers and I knew that we would always be each other’s best friends. Regardless of where we were and when we moved from one country to another, even if we had to say goodbye to our friends, we moved together with our family members. No matter where we would end up as adults, we were bound together by those memories from Madagascar or Ghana.

The food connection is also important as the chapters indicate how they are connected by memories of a place we lived; but the food we ate there and the people we knew there came from a variety of places. You will not find only recipes from Ghana in the Ghana chapter, for example, or recipes from Sri Lanka in the Sri Lanka chapter, because that is not how we lived.

3. Your book opens with five adinkra, which are symbols used by the Akan people of Ghana. Why was it important to you to include the ones you selected? What do they mean to you?

“FIHANKRA” adinkra symbol, meaning house or compound

Carell Laurent: These particular symbols represent what were the phases of our lives (through my eyes) when we were in each country. For example, the first symbol FIHANKRA, represents a house or a compound. I remember my life in Ghana being very secure and protected.

Each symbol I selected fits with my understanding and approach to life at the time of the described chapter.

4. Whom did you intend your readers to be, and what feedback have you received so far?

Carell Laurent: This book was written for my family, and they are loving it. Some members are too young to be cooking yet, but they love the stories. Some of the older members are expressing joy that they can cook something they remember having in the past but didn’t know how to make. A few non-family members have expressed surprise at something, not knowing about some connection between my parents, for example. Everyone wishes there were more pictures in it though. Perhaps that wish will serve as inspiration for a new project sometime down the road.

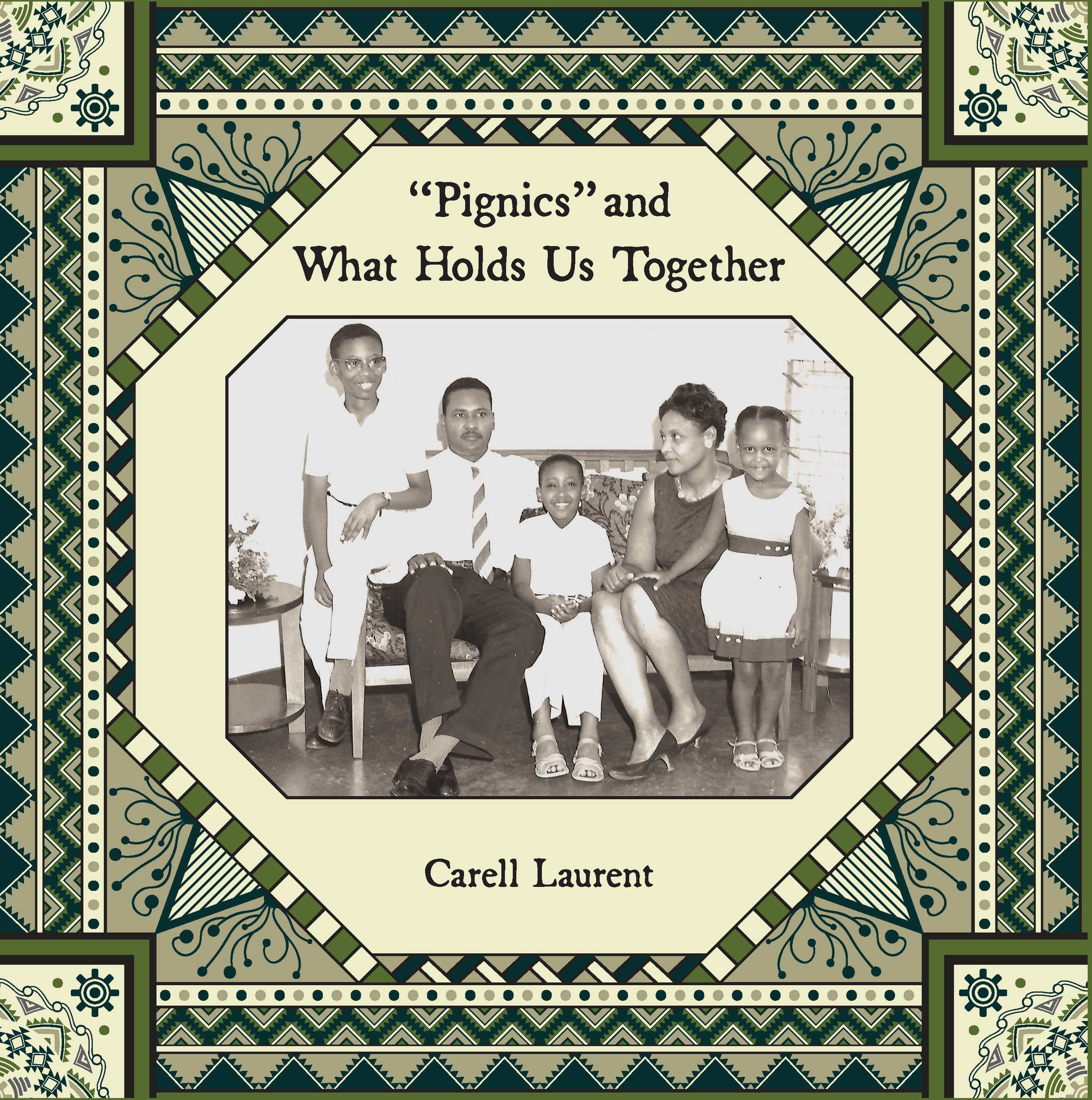

For the cover, the author simply sent a favorite photograph and said she likes the color olive green. Book Designer Nicole Miller worked her magic from there. The author also said she wanted a hardcover book that would lie flat when opened. The solution was a covered-spiral binding that makes it easy for readers to follow the recipes straight from the pages.

Liz Sonnenberg is genealogist for Modern Memoirs, Inc.