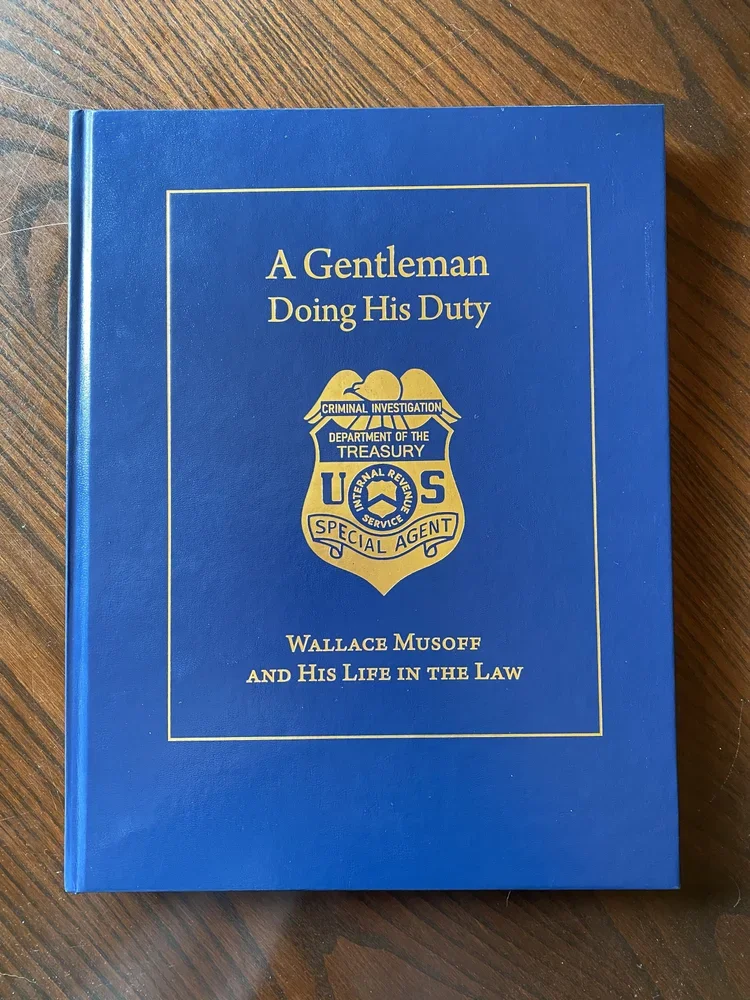

Jay K. Musoff, son of Wallace Musoff, collaborated with his brothers, Scott D. and Adam L. Musoff, to publish A Gentleman Doing His Duty: Wallace Musoff and His Life in the Law with Modern Memoirs in 2020. This collection of the court records of legal cases tried by their father took three and a half months from the day we started it until books arrived on their doorsteps. Modern Memoirs President Megan St. Marie reflected on the project shortly after its completion in 2020 in a blog entitled “On the Important Things in Life.” We recently caught up with Jay Musoff to ask what the publication process was like for him, and what it has meant to share his father’s book with others.

1. You created this book as a gift to your father to mark his 90th birthday. It spans his legal career with the U.S. Treasury Department in the 1950s and 1960s, and private practice from the 1970s to the 1990s. What inspired you to create a custom hardcover book of his court records, including family photos, news articles, and a collaborative introduction and epilogue by you and your brothers, as opposed to producing a standard volume of law reports?

Jay Musoff: Our father had a prominent and colorful legal career—involving some notable and notorious figures. Dad always had great stories about his cases, and we wanted to collect those cases, along with some memorable stories, in one place that could be shared with his family, particularly his grandchildren.

2. What was your father’s reaction when you presented him with the book?

Jay Musoff: Dad’s 90th birthday was in April 2020, and Mom had planned a big birthday celebration. COVID-19 ruined those plans. Instead, we had to celebrate Dad’s 90th birthday by Zoom. We had shipped the book to my parents’ house, and we had Dad open the box during the Zoom celebration. Dad was literally speechless. He said that the book was “breathtaking” and the best present he ever received.

“Each year since my dad has been gone, I reread the book on his birthday.”

3. What feedback have you gotten from other family members?

Jay Musoff: Dad inscribed copies of the book to all his children and grandchildren, plus some friends who are mentioned in the book. The grandchildren particularly loved some of the stories and the pictures we included in the book of their grandfather “back in the day.”

4. The cover of the book features a custom-designed image of the badge of a special agent with the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Why did you choose that emblem to represent the whole?

Jay Musoff: Dad was enormously proud of his service to our country, and the special agent badge represented that pride.

5. Your father passed away in 2023, three years after you published his book. What did it mean to you to complete it in time for his milestone birthday in 2020? How have you reflected further on the project since his passing?

Jay Musoff: We could think of no better way to mark Dad’s 90th birthday than this book that both commemorated and celebrated our father. Dad loved the book and kept copies in his office, and on the coffee tables in the living room and den room of his home. Each year since my dad has been gone, I reread the book on his birthday.

Liz Sonnenberg is staff genealogist for Modern Memoirs, Inc.